(Wikipedia: US military bases on Okinawa)

John Pomfret and Blaine Harden report for the Washington Post.

When the Democratic Party of Japan roared to victory in August, unseating a party that had run Japan almost without interruption since the 1950s, Obama administration officials fanned out across Washington with an unexpected message, given their campaign embrace of change.

U.S. relations with Japan, the message went, were going to stay basically the same.

Yes, the DPJ had run on a promise of ending Japan's decades-old pattern of "passive" behavior in its dealings with the United States. Yes, a few days before his party's victory, Yukio Hatoyama, who would become Japan's new prime minister, launched a jeremiad against U.S.-style capitalism, and advanced a contradictory view of Asia in which the United States appeared at once welcome and unwanted. Still, administration officials argued, the U.S. security relationship with Japan -- which for almost 60 years was the cornerstone of U.S. policy in Asia -- would be business as usual.

But three months later, after a trip to Tokyo by President Obama and numerous American officials, the administration is still struggling to find its way with Japan -- unaccustomed, observers say, to a Tokyo government without a static foreign policy.

The challenges were on display this week in Japan, where U.S. and Japanese officials met again Friday to deal with the latest wrinkle in their relationship -- a dispute over a $26 billion plan to move U.S. troops off and around the southern Japanese island of Okinawa. The meeting ended with no apparent agreement.

The Futenma dispute

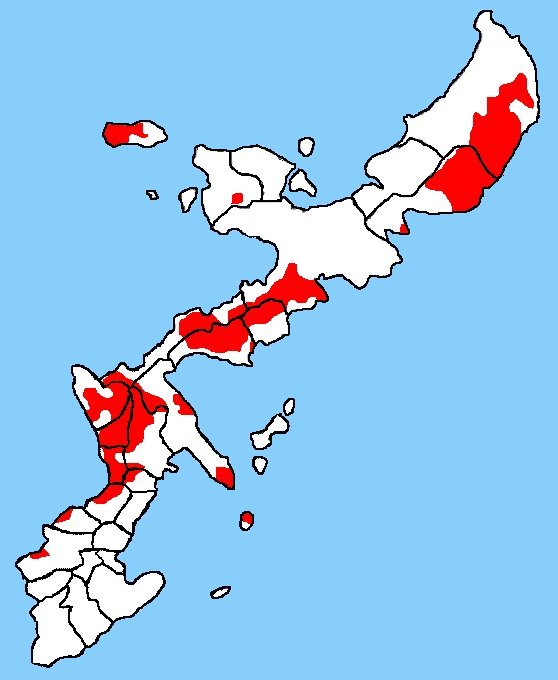

Okinawa hosts most of the 36,000 U.S. military personnel based in Japan, and the Futenma Marine air station, located in a densely populated part of the island, has become a symbol of the noise, pollution and crime that many Japanese associate with the American military presence. Under the terms of the deal, Futenma would be moved from the center of a city to Okinawa's relatively unpopulated southeastern coast. But Okinawa voted unanimously in August for DPJ candidates who opposed the deal and want a smaller American footprint on an island where 19 percent of the land is occupied by U.S. forces.

Before the meeting Friday, U.S. Ambassador John Roos said in his first public speech in Japan since he arrived three months ago that the Obama administration expects Japan to move "expeditiously" to resolve the Futenma dispute. He used "expeditiously" twice, the same word Obama used repeatedly when he visited Japan last month and called for prompt action on the base controversy.

But Hatoyama's government made clear this week that it has no intention of meeting the Americans' hurry-up-and-decide demands.

"We are not discussing this on the premise that it has to be decided by the end of the year," Hatoyama told reporters.

A big reason is that Hatoyama this week faced the prospect of a revolt by a coalition partner whose votes he needs to pass legislation in the upper house of parliament. The leader of the Social Democratic Party, Mizuho Fukushima, said her party might quit the coalition if Hatoyama honors the deal to move the Futenma air station.

'Domestic politics matter'

The threat left Hatoyama squeezed between domestic political imperatives and U.S. expectations -- a spectacle U.S. officials are not accustomed to seeing in Japan.

Daniel Sneider, a Japan expert at Stanford University, said the United States has yet to really take into account the significance of the political changes wrought by the August election. "Domestic politics matter in Japan now in a way that they didn't when you had a virtual one-party state for 50 years," he said. "Do elections and domestic politics influence foreign policy in the United States? Of course. Now they do in Japan, too."

Sneider said American officials need to give Japan more time.

But the problem, according to the officials, is that time could just make an Okinawa deal more complicated.

For example, the mayor of the town to which the Marine base is supposed to be moved backs the relocation plan. But he is up for reelection in January, and his opponent, who is favored, is less inclined to welcome the Marines. Okinawa will also elect a governor next year, and so far none of the candidates appears to support the relocation deal.

A senior administration official said he thinks Japan's new leaders will ultimately agree to the deal, given the enormous public support for the security alliance with the United States. "It'd be very destructive to them domestically to be seen as casual or indifferent to the alliance," he said. "In Japan, it would be a dominant national issue, and so I think the Japanese leadership has a huge stake in not being seen as mismanaging this issue."

Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates said in October that if Japans backs out of the deal, the U.S. military would cancel a planned move of 8,000 Marines from Okinawa to Guam and refuse to give back several parcels of land to the Okinawans. [Editor: Emphasis mine. When you're refusing to return someone their own land, that's a sign you're doing something wrong.]

But having weighed the threats, Hatoyama appears focused on putting off a decision on the air station -- even if it means annoying the United States -- to hold his ruling coalition together.

"I have to take [the Social Democratic Party] seriously," he told reporters Thursday night.

The threat to Hatoyama's legislative agenda is real, analysts said.

"If the Social Democratic Party leaves the government, he will lose his majority in the upper house, and that means no new laws can be passed," said Minoru Morita, an analyst in Tokyo. "If that happens, the cabinet will collapse. Hatoyama thinks the United States should be kind enough to wait on the base issue until this political problem is solved."

Harden reported from Tokyo.

No comments:

Post a Comment